United States president Donald Trump signed in December 2017 the “Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018,” informally known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. We discuss the impact the changes will have on both corporations and individuals.

Key Changes

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act contains the most significant revisions to the U.S. Tax Code in decades. It will substantially change how U.S. corporations are taxed, make modifications to the taxation of individuals and effect the manner in which international transactions are taxed. Areas of uncertainty will need to be clarified by regulations and notices issued by the U.S. Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Service.

Some key changes are detailed below.

- The new federal corporate income tax rate drops to 21%, down from 35%.

- Allowances are now made for immediate expensing of most types of depreciable property other than real estate. As a result, corporate taxpayers can claim a 100% deduction in the year a property is placed in service, rather than having to depreciate it over time.

- U.S. corporations are subject to a modified "territorial" system of corporate taxation, where certain off-shore earnings are not to be subject to corporate tax in the U.S., and taxed at lower rates.

- The changes make the U.S. a more attractive location for a parent of a multi-national enterprise and will level the playing field somewhat compared to other jurisdictions.

Inbound Investment in U.S. Real Estate

The Act improves the tax landscape for inbound investment in U.S. real estate. Now, investments made by corporations or through entities treated as corporations (otherwise known as Blockers) will benefit from the new lower corporate rate.

The changes make the U.S. a more attractive location for a parent of a multi-national enterprise and will level the playing field somewhat compared to other jurisdictions.

As a results of the changes, real estate businesses will now generally be exempt from both the old and new earnings-stripping rules of section 163(j) (with real estate business being generally defined fairly broadly). This will allow for the use of cross-border leverage to reduce U.S. net basis tax and take advantage of exceptions from U.S. withholding tax for "portfolio interest" and under provisions of double tax treaties such as Article XI of the U.S. Canada Income Tax Treaty. It is worth noting that more restrictive earnings-stripping rules that would have applied to real estate subsidiaries that were part of certain international groups were dropped from earlier versions of the Act and did not become law.

Private Equity Funds

In terms of private equity, new carried interest rules impose a new three-year holding period for carried interest holders to benefit from capital gain rates. This means private equity fund sponsors may not want to sell any assets until at least three years after they are acquired.

Private equity fund sponsors may not want to sell any assets until at least three years after they are acquired.

Corporate Blockers used by funds will benefit from the new lower corporate rate, but will be subject to the new restrictive earnings-stripping rules with respect to non-real-estate businesses, which will limit interest deduction to 30% of EBITDA.

Full expensing of most depreciable property other than real estate will help lower effective tax rates for Blockers and taxable investors. Taxable U.S. investors will benefit in many scenarios from a new lower effective tax rate for pass-through income from active businesses.

Funds may be more reluctant to sell Blocker shares for reasons discussed under M&A below, and because the tax leakage inside the Blocker on an asset sale will be lower.

Secondary purchases and sales of interests in funds will have to deal with new rules that impose tax on gain from a sale by a non-U.S. resident on interest in a fund to the extent that a sale by the fund of its assets would have produced "effectively connected income."

A 10% withholding tax will also apply to the sale unless no portion of the gain would be treated as effectively connected income under the new rules. The manner of certifying that the withholding tax does not apply is not specified in the Act and will have to be developed through regulations. This withholding rule may significantly complicated secondary sales.

M&A

The new rules allowing immediate expensing of acquired assets may tilt the field toward asset acquisitions (or transactions treated as asset acquisitions for tax purposes) rather than stock acquisitions.

Eliminating net operating loss (or NOLs) carrybacks may cause some sellers to ask buyers to make "tax receivable" payments if and when the buyer uses the NOLs in future periods.

New restrictions on transferring assets used in a U.S. business to non-U.S. entities will make tax-free outbound M&A more difficult and may lead to more taxable transactions or structures that don't involve outbound transfers.

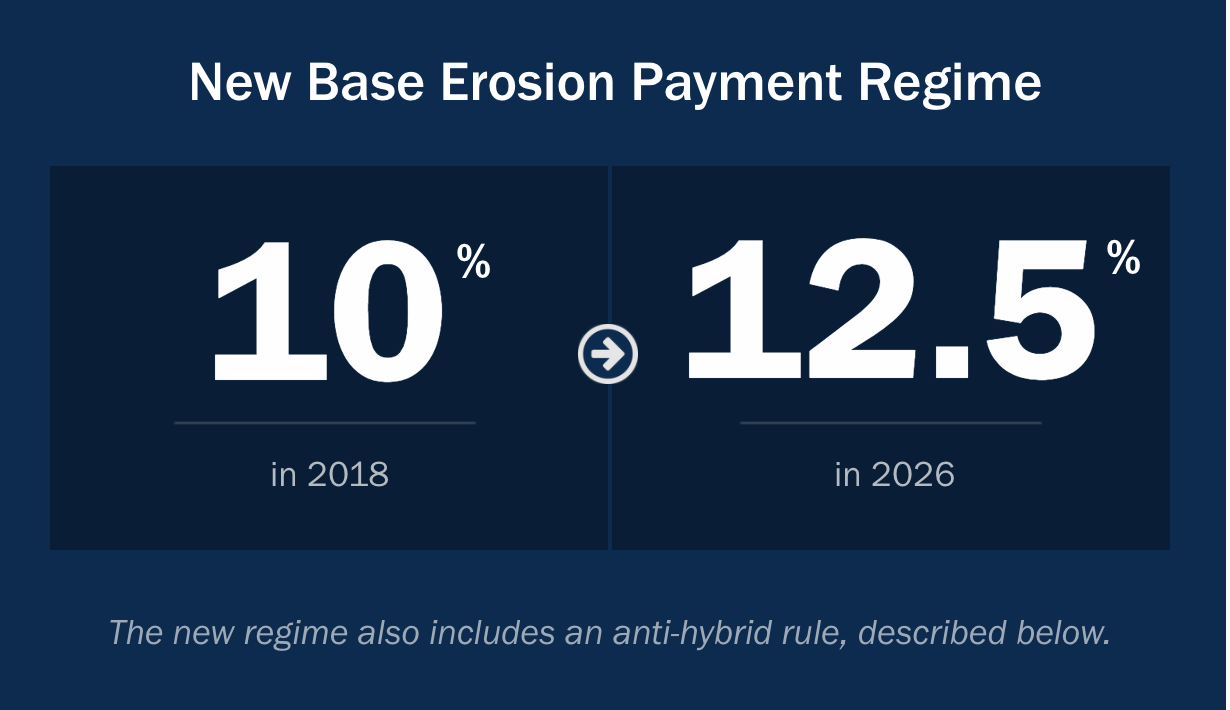

New base erosion payment regimes will make cross-border structures require more analysis to determine if payments among related parties trigger the new base erosion tax.

Cross-Border Payments

A base erosion payment regime will impose an alternative tax on corporations that make deductible payments to related foreign affiliates. The regime effectively functions like an excise tax (generally 10%, rising to 12.5% in 2026) on certain payments to related non-U.S. parties.

An additional base-erosion anti-hybrid rule will deny a deduction for cross-border payments from U.S. entities to offshore entities or branches through "hybrid" entities or branches. These are treated differently in non-U.S. jurisdictions than they are in the U.S.

Subscribe and stay informed

Stay in the know. Get the latest commentary, updates and insights for business from Torys.

Stay in the know. Get the latest commentary, updates and insights for business from Torys.

Subscribe Now