Although not required by law, the inclusion of financial forecasts in Canadian IPO prospectuses has become commonplace–a necessary tool to market and price an offering successfully.

Once public, issuers will typically continue to include the forecast in their continuous disclosure filings (effectively reaffirming the forecast). While forward looking financial information like forecasts can be very helpful to the market, it is also disclosure that carries inherent risks: when that disclosure has to be revisited, the effects on an issuer can be significant and negative. But, when does an issuer have to reconsider a forecast, and either update it or withdraw it altogether?

Canadian securities law requirements

Canadian securities laws require the disclosure of forward-looking information (FLI) only in connection with some aspects of management’s discussion and analysis. Other FLI disclosure, including forecasts, is voluntary. However, if an issuer chooses to provide FLI in its disclosure, including a forecast in an IPO prospectus, it is subject to the following restrictions:

- the issuer must have a reasonable basis for the disclosure;

- the FLI must also be accompanied by disclosure that identifies it as FLI, and that cautions that actual events and circumstances may lead to results that differ from the FLI; and

- the issuer must disclose the factors used to develop the FLI and include the issuer’s policy for updating that disclosure.

As financial FLI, forecast disclosure is also subject to the requirement that it should be limited to a period in which the information can be reasonably estimated.

Length of forecasting

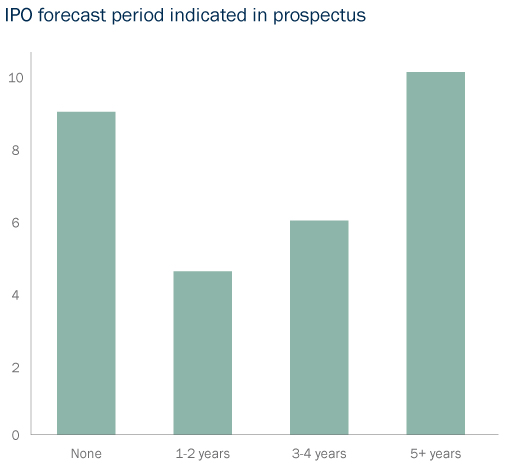

A review of recent IPO prospectus disclosure reveals that (i) this voluntary disclosure is made frequently by issuers (with only 1/3 of issuers foregoing including forecasting disclosure) and (ii) the forecasts that are included in this disclosure can cover anywhere from one to as many as seven years.

The length of time covered by a forecast, in particular, has attracted regulatory scrutiny. The 2016-2017 annual report of the Corporate Finance Branch of the Ontario Securities Commission noted that issuers had been disclosing FLI that went beyond the issuer’s next fiscal year without providing reasonable and sufficient assumptions to support the disclosure. In 2018, the Canadian Securities Administrators issued CSA Staff Notice 51-355 that also addressed concerns with lengthy forecast periods, emphasizing the need to disclose the qualitative and quantitative assumptions underlying a forecast. The notice warned that, for example, “an issuer projecting aggressive growth targets without the benefit of historical experience should be able to show (i) a reasonable basis for those targets, including the key drivers behind the projected growth with reference to specific plans and objectives that support the projected growth, and (ii) why management believes that each of the targets/FLI are reasonable.” In an appropriate case, staff has said they will require an issuer to change its forecast disclosure. A forecast or other FLI that does not comply with the regulator’s guidance could also result in administrative enforcement proceedings.

The length of time covered by a forecast, in particular, has attracted regulatory scrutiny. The 2016-2017 annual report of the Corporate Finance Branch of the Ontario Securities Commission noted that issuers had been disclosing FLI that went beyond the issuer’s next fiscal year without providing reasonable and sufficient assumptions to support the disclosure. In 2018, the Canadian Securities Administrators issued CSA Staff Notice 51-355 that also addressed concerns with lengthy forecast periods, emphasizing the need to disclose the qualitative and quantitative assumptions underlying a forecast. The notice warned that, for example, “an issuer projecting aggressive growth targets without the benefit of historical experience should be able to show (i) a reasonable basis for those targets, including the key drivers behind the projected growth with reference to specific plans and objectives that support the projected growth, and (ii) why management believes that each of the targets/FLI are reasonable.” In an appropriate case, staff has said they will require an issuer to change its forecast disclosure. A forecast or other FLI that does not comply with the regulator’s guidance could also result in administrative enforcement proceedings.

All forecast disclosure is subject to the risk that events and circumstances do not unfold as anticipated—that targets are not met. This risk is heightened where the forecast period is lengthy. Where the future deviates from expectations reflected in a forecast, issuers may have to make disclosure that revisits the forecast. The market saw that the effect of revised forecast disclosure can be significant in the last quarter of 2018: when Freshii Inc. withdrew its forecast disclosure regarding store count, sales growth and similar targets, the market reacted swiftly, significantly and negatively.

When does an issuer have to revisit its forecast? If there is a material change in the issuer’s business, operations or capital that affects a forecast, that material change must be disclosed immediately. However, less profound developments may also require that an issuer update its forecast. In its MD&A, an issuer is required to update a forecast if events and circumstances that occurred during the reporting period are reasonably likely to cause actual results to differ materially from the FLI in the forecast. Like all disclosure revisions, updating forecasts carries the risk of litigation. While not required to provide an intra-quarterly update on a forecast, Danier Leather Inc. chose to do so shortly after its IPO, resulting in a significant and negative market reaction, and a class action.

The duty to update does not extend to disclosure consisting of vague expressions of optimism about future developments in the issuer’s business, or to what the courts have described as “an ordinary earnings forecast.”

An issuer may also conclude that it has to withdraw its forecast altogether, as Freshii did. If a forecast is withdrawn, the issuer must explain the withdrawal decision, including highlighting the events and circumstances that led to the decision to withdraw the forecast and discussing why the assumptions underlying the forecast are no longer valid. Freshii’s recent experience, and that of other issuers before it, highlights the risks of voluntary forward-looking financial disclosure, reminding issuers and underwriters to carefully assess and test any outlook (especially quantified information) and consider if a risk-reward analysis supports its inclusion in an IPO prospectus (or in any continuous disclosure filings). Even a reasonable and well-considered forecast may not be achieved, and the reasonableness of the assumptions underlying the forecast may be judged with the benefit of hindsight.

U.S. perspective

Despite the inherent risks, forecast disclosure continues to be made voluntarily in response to market demands. It can be helpful disclosure for investors. In order to address the risk of forecast disclosure while encouraging issuers to make it, Canadian securities law includes defences to civil litigation specifically tailored to FLI. In connection with a claim alleging prospectus misrepresentations, an issuer has a defence in respect of FLI disclosure if it had a reasonable basis for the FLI, and included appropriate cautionary language. A similar defence is available in respect of FLI in continuous disclosure.

As is the case in Canada, under U.S. securities laws an issuer does not have an affirmative obligation to disclose forecast information or other forward looking financial information, other than where the MD&A requires it. Unlike the law in Canada, if an issuer in the U.S. volunteers forecast disclosure, there is no statutory duty to revise it. However, U.S. caselaw has developed a duty to correct, and a duty to update, forecast disclosure in certain instances. Courts in the U.S. have found that where an issuer learns that a forecast or other forward looking financial information contains an error at the time the disclosure was originally made, there is a duty to correct that error. This is premised on an implicit representation in a forecast that errors will be corrected.

In limited circumstances, an issuer may also be found liable to investors if it fails to update forecast and similar future-oriented disclosure to reflect events after the disclosure was originally made. The duty to update a forecast may arise only if the updated information has become materially misleading in light of subsequent developments, and only if the original disclosure is “alive” in the market in the sense that a reasonable investor would be expected to rely on it. The duty to update does not extend to disclosure consisting of vague expressions of optimism about future developments in the issuer’s business, or to what the courts have described as “an ordinary earnings forecast.” The duty to update is confined to limited circumstances in recognition, among other things, that statements about the future are inherently uncertain and that issuers should be encouraged to make forecast and similar disclosure without being burdened with a requirement to refresh that disclosure continuously.

Subscribe and stay informed

Stay in the know. Get the latest commentary, updates and insights for business from Torys.

Stay in the know. Get the latest commentary, updates and insights for business from Torys.

Subscribe Now